Marine Corps Vietnam Tankers Historical Foundation®

Marine Corps Tankers and Ontoscrewmen Have Made History. Your Foundation is Making it Known.

The M50a1 Ontos

|

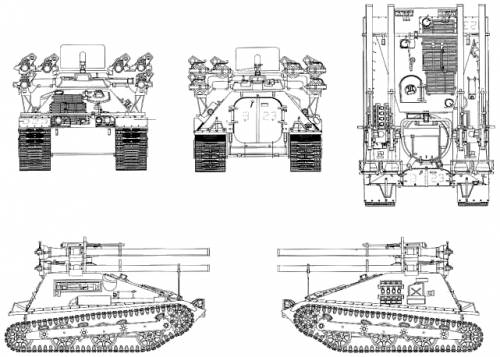

The Ontos Anti-Tank Vehicle. ©2001 Peter Brush By any measure, the Ontos was one of the most interesting “things” to come down the road of United States military armored development. The idea for this vehicle was born in the aftermath of World War II when the U.S. Army perceived the need for a new reconnaissance vehicle. Then it evolved into a tank destroyer for use with the Army on the nuclear battlefields of Europe. Next it was deployed in Marine Corps anti-tank (AT) battalions. The Ontos most significant contribution was in the Vietnam War, but in a role much different from the role for which it was designed. This is the story of the Ontos, officially the “Rifle, Multiple 106mm, Self-Propelled, M50.” The adaption of the internal combustion engine to warfare brought about the removal of the horse from the battlefield. The reconnaissance mission formerly performed by cavalry remained. By the end of World War II, the motorcycle, jeep, armored car, and light tank all tried to fill the gap, all without complete success. A classified 1953 U.S. Army report noted: “There is an urgent and immediate need in our army for a vehicle similar in performance to the jeep, but at the same time affording some armored protection and greater cross-country mobility, for use by reconnaissance personnel, commanders, messengers, and liaison officers who are frequently exposed to small arms fire.” At that time jeeps and half-tracks were authorized in the command, scout, and support elements of the Army reconnaissance platoon. The Ontos was considered as a replacement. After considerable study the Army concluded that although the vehicle had outstanding cross-country mobility and armor protection, it had deficiencies in the areas of storage space, lack of speed, lack of range, and excess weight. Ironically, given the vulnerability of the M50 to enemy mines in Vietnam, the Army concluded these test vehicles “offered protection against atomic bombing.” The Army decided to stick with its M38A1 ¼ ton trucks and M21 mortar carriers for reconnaissance platoon use. Spurred by Secretary Frank Pace, Jr., the Army was developing the Ontos as a family of vehicles, to include infantry carrier, antitank antiaircraft, self propelled artillery and logistics carrier. During World War II, the Army embraced the tank destroyer concept, which called for the placement of large-caliber anti-tank guns on lightly armored carriages. These could quickly be moved to any area under enemy tank threat. This concept was never embraced by the Marine Corps to any extent. The tank remained the favored anti-tank weapon for the Marines in the immediate postwar period. In addition to duties as naval infantry, postwar planners envisioned a role for the Corps in any European conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. Late 1940s war planning put the Marines into direct conflict with front-line units of the Red Army. In the Pacific War the Marines dealt with sporadic attacks by small Japanese tanks. In the future war Marine tankers would have to face a highly mechanized Soviet force equipped with large numbers of medium and heavy tanks. Using tanks to destroy enemy tanks proved less than satisfactory in the Korean War: too often the weight of American medium tanks rendered them too road bound. Marine planners, cognizant of the formidable threat posed by Communist armor, returned to the World War II tank destroyer concept. In 1949 the USMC Armor Policy Board specifically noted “There is a requirement for a destroyer-type tank to destroy hostile heavily armored vehicles….” As early as 1944, Army production and logistics considerations began to determine Marine Corps tank decisions. Although some of the USMC armor requirement was developed and produced by the Navy’s Bureau of Ships (e.g., amphibious tractor or amtracs), the Corps came to fully depend on the Army for its tank procurement. In 1951, based on an Army initiative, Allis Chalmers became the lead contractor for this new anti-tank vehicle. It would be built at the company’s La Porte, IN, factory. In 1953, Michigan Congressman Gerald R Ford held congressional hearing for Army appropriations. When discussion turned to anti-tank capabilities, the testimony of Army generals was taken off the record and not included in the printed transcript. The public became aware of Ontos development only by mistake. According to a report in the New York Times dated June 26, 1953, the congressional testimony was classified “Secret”. The newspaper noted “An entirely new weapons-carrying vehicle, nicknamed ‘The Thing’ but carrying the official designation Ontos, to be used variously, including as a mount for a new ‘highly-powered’ recoilless rifle and for a quadruple .50 calibre antiaircraft weapon against low flying planes.’ Army officials expressed amazement and appeared appalled when copies of the 1,667-page printed testimony released by the subcommittee reached the Pentagon. The first production model of the M-50 came off the assembly line on 31 October 1956. The original Ontos emphasized firepower over crew comfort. The hull was derived from the T55/T56 series of tracked armored personnel carriers. It was powered by a six cylinder in-line gasoline engine, the General Motors SL 12340, which developed 145 horsepower at 3,400 rpm (this was later upgraded to a Chrysler V-8). This power source was coupled to a XT-90-2 transmission, which drove the front sprockets, which turned the tracks. Maximum road speed was 30 mph on improved roads. The Ontos had terrain navigation ability superior to tanks. Range was 190 miles on primary roads, 120 miles on secondary roads, and 50 miles cross country with a 47 gallon internal fuel tank. With fording kit installed the vehicle could cross streams as deep as 60 inches. The vehicle weighed nine tons. It had a three man crew: driver, loader, and gunner. For a tracked vehicle it made little noise. Consequently, there was no intercom between the gunner and driver, although there was a loudspeaker on the radio. The M-50 was not portable by an available helicopter although it could be air transported by R4Q aircraft. Two Ontos could be landed over the beach in a LCM-6 (Landing Craft, Mechanized). The M-50 could climb a 60 percent grade climb over a 30-inch obstacle. The engine would run wet, and the vehicle could ford two feet of water in normal configuration. With fording equipment it could go deeper. The main weapon consisted of six 106mm M40A1C recoilless rifles mounted on a central turret. The guns extended beyond the hull on both sides. Built with simplicity in mind, this rifle was the same weapon used by infantry on a fixed mount. These guns could be fired individually, in pairs, or all at once. Fifty caliber spotting rifles were mounted on four of the recoilless rifles. Two of the recoilless rifles were equipped with a spotting rifle and sight and could be removed from the vehicle for use on ground mounts (these spotting rifles could not be fired from inside). The sights and could be removed from the vehicle for use on ground mounts. The Ontos also had a .30 caliber machine gun. Each vehicle carried a normal load of 18 rounds of 106mm ammunition (six in the rifles plus a dozen more in the ammo bin). These weapons were externally and coaxially mounted and were fired electrically. The rate of fire was four aimed rounds per minute with all guns loaded and fired individually. The trajectories of the spotting rounds and the 106mm rounds were very similar to a distance of 1,100 yards. Beyond 1,100 yards the trajectories differed, causing the effectiveness of this spotting system to decrease as range increased. The spotting rifle could not be used beyond 1,500 yards, necessitating the use of burst-on- target and bracket techniques of fire adjustment at these greater ranges. High Explosive Anti-Tank (HEAT) ammunition for the 106mm rifle would penetrate the armor of any known tank (16” of armor at 0 degrees obliquity). The Ontos’ armor was one-half inch plate except for the floor, which was only 3/16” inch thick. The upper sloped armor would withstand all small arms fire, but was vulnerable to .50 caliber armor piercing rounds. Artillery airbursts could cause severe damage to the Ontos’ guns and external fire control equipment. Frank Pace, Secretary of the Army during the Truman administration, initially supported the M50 for Army use. Pace noted, “If Ontos is there, tanks had better get the hell off the battlefield.” Not everyone agreed with Pace. Others felt it was too lightly armored, underpowered, and incapable of sustained combat. The Marine Corps accepted the Ontos after the Army rejected it. The Marines did not have the specialized supply and maintenance capabilities of the Army, and the Ontos was a simple vehicle. It had fewer parts than other armored vehicles. There was no heavy turret. The engine was a common truck engine found on various military and civilian vehicles. The fire control system was simple: according to LtCol. E.L. Bale, Jr., a Marine instructor at the Army Armor School, the average Marine could master the system “as easily as he has the pinball machine in the local drug store.” The Corps ordered 13 million dollars worth, about 300 vehicles. Production was to run for about one year. The Ontos, manned by infantrymen, was quickly integrated into regimental anti-tank companies. These companies contained 12 Ontos, five officers, And 91 enlisted men. Each unit consisted of three Ontos platoons of four vehicles each. The unit’s 72 anti-tank rifles could be fired from the vehicle or dismounted and fired from ground mounts. Its first non-training deployment abroad came in July 1958. The Lebanon Crisis saw Marine Battalion Landing Teams (BLT) of the Navy’s Sixth Fleet come ashore to stabilize the weak Lebanese national government. This 2nd Provisional Marine Force included 15 M48 tanks, 10 Ontos, and 31 LVTP5 amtracks (Landing Vehicle, Tracked). These vehicles provided general Force security and protection for armored patrols until a larger Army tank force could be sent from Germany. The Marines began reembarkation in mid-August. The Ontos next saw action in 1965 in the Caribbean. In April the Dominican Republic was sliding into civil war as reformers did battle with right-wing military forces. The 6th Marine Expeditionary Unit, the Caribbean quick-reaction force, was ordered to ashore in order to evacuate civilians and reinforce security at the American embassy. A company each of tanks and amtracs (LVTs) plus two platoons of Ontos were part of the landing team, which took the side of the Dominican military. Ontos were organized in the Marine Division into Anti-Tank Battalions. Each battalion was composed of one headquarters and service company plus three anti-tank companies. Each of these letter companies contained three platoons of five Ontos for a total of 45 Ontos vehicles per battalion. Planned distribution in the Marine Division was for a company of 15 Ontos (three platoons) for each of the division’s three infantry regiments. Ontos companies, along with tanks and amtracs, landed with the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade at Da Nang, Vietnam, in the first half of 1965. Within one year, both the 1st and 3rd Anti-Tank Battalions were ashore in Vietnam. Unlike the enemy in the Korean War, the Vietnamese Communist military forces possessed significant anti-armor capabilities in the form of recoilless rifles and rock propelled grenades. The Ontos’ thin floor armor (3/16”) made it especially vulnerable to mines. Consequently, and as opposed to its designed role, Ontos spent a great portion of their time in static defense positions. Initially Ontos units were deployed in defense of the Da Nang airfield. In August, 1965, the Marines began Operation Starlite, the first big battle of the war. At 0730 on August 17, tanks and Ontos rolled off amphibious landing craft (LCUs and LCMs) and made their way ashore south of Chu Lai in support of the assault companies. Later in the day a Marine armored column was halted when a M-48 tank was hit with recoilless rifle fire. The Viet Cong (VC) poured mortar and small arms fire into the Marine positions, quickly killing five and wounding 17. The Ontos maneuvered to provide frontal fire and flank protection until enemy fire let up. The following month, in Operation Golden Fleece, a combined infantry-armor assault force including Ontos attacked a VC main force unit trying to collect a rice tax in a Vietnamese village near Da Nang. The enemy was forced to break contact and flee the area. After establishing themselves at Da Nang and Chu Lai, the Marines built their third base at Phu Bai, in Thua Thien Province 35 miles northwest of Da Nang. Initially, defense of Phu Bai was provided by the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines (Reinforced) which had a platoon of M50s attached. It was not only the Marines who were expanding their forces in the northern part of South Vietnam: both the VC and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) also increased their forces, and both sides sustained heavy casualties. In late June, on Operation Jay, a large, heavily armed VC force ambushed a South Vietnamese Marine Corps convoy moving north on Route 1, the main north-south highway in Vietnam. At 0830 hours on June 29, the attacking force struck the convoy with mortar and recoilless rifle fire, quickly hitting ten trucks. U.S. Marines quickly sent reinforcements, including Ontos, to assist the SVN Marines. The VC force lost interest and tried to break contact. While crossing open ground, the M50 platoon opened fire and “obliterated a VC squad on a ridgeline with a single 106mm salvo.” A M50 platoon commander even captured an enemy soldier. Over 185 enemy soldiers were killed in this action. Marines and their armor were deployed in I Corps, the northernmost of four military districts in Vietnam. An exception to this was Special Landing Force (SLF) of the Navy’s Seventh Fleet, the strategic reserve for the Pacific Far East. The SLF was available for amphibious landings in South Vietnam. Gen. William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, decided to use the SLF to clear Viet Cong forces from the Rung Sat Special Zone south of Saigon. VC gunners were firing on ships using the river channel that supplied the Vietnamese capital. The result was Operation Jackstay, March 26-April 6, 1966. The operation had limited success but not due to lack of ingenuity of the Marines, who experimented with riverine warfare techniques including mounting an Ontos on a LCM to provide fire support. Only 63 enemy troops were killed; however, the shipping channel was at least temporarily clear. The following incident illustrates the vulnerability of the M50 to enemy mines. It was spring, 1966. An armored column supporting Company “K”, 3/9 was returning to base camp near Da Nang. Three tanks and an Ontos went over a stream at a place called Viem Dong Crossing without mishap. As the second M50 crossed, Platoon Commander Lt Allen Hoof heard a “pop”, turned rearward, and saw the upper half of the vehicle blown off the lower half, and lying upside down next to it. All three crewmen were wounded. Acting Ontos Commander PFC Greg Weaver was quickly removed from the vehicle but died almost immediately. The mine explosion, perhaps either command detonated or activated by a counter, caused the detonation of a 106mm round stored directly under the commander. This secondary explosion blew the turret off the vehicle and killed Weaver. Since enemy tanks were not a problem for Marines in Vietnam, Ontos use reverted to its secondary mission: providing direct fire support for infantry. By late 1966 problems with Ontos became evident. The supply of tracks was depleted, which caused breakdowns on operations. This caused a reluctance to utilize the M50. An even more important reason was several incidents of accidental firings of recoilless rifles which cost some Marine lives. This was an extremely serious problem for Ontos on convoy duty. These accidents were caused by overly tight adjustment of the firing cable allowing the firing pin to release prematurely. This adjustment was a crew responsibility and required thorough understanding of the firing cable, sear, and trigger. These mishaps caused restrictions to be placed on Ontos’ use. By 1967 the Marines were fighting two wars in Vietnam. The 1st Marine Division engaged in counter guerrilla operations in the southern part of I Corps while the 3rd Marine Division conducted mostly conventional war against NVA along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) in the north. As the Marines moved northward to counter the NVA threat, Ontos and tanks provided important support. In May 1967, the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines (2/9) and 2nd Battalion, 26th Marines (2/26) began Operation Hickory north of Con Thien. Fighting against enemy forces in well prepared bunkers and trenches was heavy. M50s, using the proper ammunition, proved to be devastating antipersonnel weapons. After the conclusion of Hickory, 2/9, accompanied by tanks and Ontos, was sent on a spoiling attack into the DMZ. On this operation the tracked vehicles proved more of a liability than a tactical asset as the terrain restricted them to the road. Instead of providing infantry support, the M50s and tanks required infantry protection against NVA rocket propelled grenade (RPG) attack. Using these vehicles as ambulances to evacuate the wounded further reduced their offensive capabilities. 1967 saw the introduction of CH-53 Sea Stallion heavy-lift helicopters for the Marines in Vietnam. The first models had a six-ton external lift capability. This meant an Ontos could be transported by helicopter if it was broken down into components with the hull transported externally. It could then be reassembled and operated at destination, giving it a transportability beyond its design considerations. M50s could also go where tanks feared to tread (or should have): in a 1966 operation, tanks got stuck in flooded rice paddies. Ontos, with less ground pressure, were able to drag timbers up to the tanks without bogging down. In Operation Jay, mentioned above, the Ontos of B Company, 3rd Anti-Tanks were able to assist the SVN Marines because they could cross a pontoon bridge - - the only tracked vehicles light enough to drive to the operation. Ontos could go more places than many people thought possible. In December 1967, the 1st and 3rd Anti-Tank Battalions were de-commissioned in Vietnam. One company from each battalion was attached to the tank battalions. 1968 saw Ontos assume an important role in some of the heaviest fighting of the entire war, the Battle of Hue during the Tet Offensive. In February, 14 NVA battalions seized control of most of the city. The Americans and South Vietnamese faced the formidable task of retaking this important cultural center of the nation. The result was urban fighting unlike anything seen in the war. The attacking Marines had to take each building and each block one at a time. This close-quarter combat and low flying clouds, coupled with the desire to minimize damage to the city itself, meant there could be little reliance on artillery and close air support. Four tanks from the 3rd Tank Battalion along with a platoon of Ontos from the Anti-Tank Company, 1st Tank Battalion, joined the advance against strong enemy resistance. LtCol Ernest Cheatham, commander of 2/5, had reservations about using tanks. One tank sustained over 120 hits and another went through five or six crews. Infantry commanders liked the Ontos better. Cheatham described the M50 “as big a help as any item of gear we had that was not organic” to the battalion. Regimental commander Col. Stanley Hughes went even further when he claimed the Ontos was the most effective of all the supporting arms the Marines had at their disposal. Its mobility made up for its lack of armor protection, noting that at ranges of 300 to 500 yards, its recoilless rifles routinely opened “4 square meter holes or completely knock[ed] out an exterior wall.” The armor plating of the M50 was sufficient protection against enemy small arms fire and grenades. However, B-40 ant-tank rockets were another story: an Ontos with 1/1 was knocked out and the driver killed on February 7 while supporting the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines. The essential role of tanks and M50s in the fighting illustrated by the fact that Marines had to hold up their advance from time to time for lack of 90mm tank and 106mm Ontos ammunition. The Perfume River flows through Hue. After clearing the south bank on February 11, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines pushed north to clear NVA forces firmly entrenched in the 4-square-mile Citadel, location of the former Imperial Palace. USMC M-48 tanks and Ontos were placed under the command of the attached tank platoon commander. Tactically, the tank or Ontos commander, working with the infantry commander, would reconnoiter a particular target area, usually a masonry structure blocking the Marine advance. Returning to their vehicle, the tank or Ontos commander would move forward at full speed while the infantry laid down a heavy volume of fire. Upon reaching a position where fire could be directed on the target, the vehicle commander halted the vehicle, fired two or three rounds into the structure, then quickly reversed direction and returned to friendly front lines. Casualties among armor crews were high. On February 24, South Vietnamese troops finally dislodged NVA forces from the Citadel. By the time the battle for Hue was over, 50 percent of the city was destroyed. Before, during, and after the Battle of Hue, the 26th Marine Regiment was fighting the North Vietnamese at Khe Sanh. Here the enemy tank threat was real: 17 days into the battle at Khe Sanh, NVA tanks helped overrun the nearby Special Forces camp at Lang Vei. Ten M50s from B Co (-) 3rd Anti-Tank Battalion were incorporated into Khe Sanh’s defenses. They were sometimes used for reconnaissance but more often in static perimeter defense roles. Author Robert Pisor notes the Ontos at Khe Sanh had “enough flechette [anti-personnel] ammunition to pin the entire North Vietnamese Army to the face of Co Roc Mountain.” The Marine Corps began to deploy its forces out of Vietnam in 1969. Tank and amtrac units rotated early as fighting had ebbed in the Corps’ area of responsibility. By this time the M50 parts supply was depleted and the 106mm rifle was about to be replaced by other weapons. M50 mechanics cannibalized disabled machines to keep others running, but after Hue the Ontos were worn out. Ironically, excess Ontos were given to Army forces (recall that the Army initially rejected the Ontos as being unsuitable for its requirements). These Army Ontos went to Company D, 16th Armor, 173rd Airborne Brigade. The Army used its Ontos until they ran out of spare parts, then employed them in fixed bunkers. In the United States, the Marine 2nd Anti-Tank Battalion was disbanded along with the 5th Marine Division. The last Ontos garrison was stationed at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. It continued to operate until 1980 by which time it had one operation vehicle. Two others were used for parts. Upon return to the United States, the tops of the vehicles were removed. Many of the chassis were sold for use as construction equipment or give to local governments for rescue work. One “platoon” of surplus M50s wound up in the service of the North Carolina Forestry Service for use as fire fighting vehicles. According to Vietnam veteran and former Marine Mike Scudder, Ontos today are scarce. In fact, there are more surviving World War I tanks than Ontos. Scudder should know: he bought the seven from North Carolina and is restoring two of them. More than 60 Ontos are believed to be stored in the desert at the Marine Corps facility, Naval Air Warfare Center, China Lake, CA. Was the Ontos a successful addition to the Marine Corps arsenal? The answer is quite simply, yes and no. The primary mission of the M50 was a tank destroyer. In the actual tactical environments in which it was deployed, there was little use for this ability. Its secondary mission was the provision of direct fire support for the infantry. In this role the Ontos was underutilized. The reason, according to Major D.C. Satcher writing in the Marine Corps Gazette, is because, unlike artillery, air, and tanks, Ontos were little emphasized in Marine officer training. Ontos were never used in any tactics problems in The Basic School. Ontos crew did not have their own MOS (instead, they were infantry MOS). An Ontos officer normally served one tour with an M50 unit, then moved on. A weapons system that is under-emphasized will be underutilized. Although quick and agile (the M50 could go places no other Marine armored vehicle could go), it had limitations. In addition to the problems previously noted (premature firing and vulnerability to mining), the recoilless rifles had to be loaded externally which meant the crew had to leave the protection of an armored hull in order to reload. The 106mm recoilless rifle is no stealth weapon: when fired, the tremendous back blast makes the Ontos’ location visible to the enemy. Ontos crew had to ensure no friendly troops were in the large back blast area when operating in confined areas. There was no enemy armor for the Ontos to destroy in Vietnam. Still, Marines are famous for their ability to improvise, and the enemy infantry were plentiful. The M50 was a formidable anti-personnel weapon. A couple of Ontos on the perimeter could decimate Communist forces attack on Marine fixed positions, a static role quite the opposite of its designed high-mobility anti-armor role. My favorite example of Marines ability to adapt to local tactical conditions is the main streets of Hue City in February 1968. Not only good at destroying structures, Ontos were able to provide a “smoke screen” for infantry attacks: when Marine artillery was unable to provide white phosphorus rounds, Ontos could fire “beehive” rounds (explosive shells filled with thousands of small darts) fired into masonry structures, thereby creating a dust cloud that screened infantry movement. Marine infantry loved their Ontos. In Phase Line Green: The Battle for Hue, 1968, author Nicholas Warr describes how the M50 platoon pounded the enemy positions, accompanied to the choruses of “Get some!” sung by infantry holed up in houses, waiting to move forward. Fact is, even with its limitations, the Ontos was used and, to a considerable degree, used up in Vietnam, providing invaluable support for the Marines in I Corps. Peter Brush Kenneth W. Estes, Marines under Armor (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000) William B Allmon, “The Ontos,” Vietnam, August 1994 Note: This article is the revision of an earlier article published in Vietnam magazine, October, 2002. It includes corrections to the original article and additional information. About the Author: Here's how he first learned of Ontos. When he was a tadpole, his father was stationed at the Marine Corps Supply Depot at Barstow, California. This was in the 1950s. He saw plenty of tanks and amtracs in their huge storage areas but the Ontos was especially interesting looking; so different and formidable, compared to anything else, even though much smaller. He saw them again next time at Khe Sanh during the siege. Often they were deployed at night facing down the long axis of the airstrip, in case the NVA decided to attack the base from that direction -- as he recalls, the airstrip extended right to the perimeter, even a bit beyond. After a few weeks of fighting, his thinking was, "come on in, NVA, and see what Ontos with beehive rounds can do!" Ah, and the rest is history And more: Peter served in the Marine artillery units in Quang Tri province from August 1967 to July 1968 with 1st Battalion, 12th Marines and 1st Battalion, 13th Marines. With 1/13 he was admin chief of Mortar Battery at Khe Sanh during the 1968 siege. He has a BA and MA in history and a MLIS degree in library science. He retired from Vanderbilt University in 2013, where he was the history librarian. He has published over 100 articles, mostly about the Marines in Vietnam. (Many of which are found on the Foundation’s web site)

|

|

Let’s Transfer Ontos to Barstow Bernard E Trainor Copy of “Let’s Transfer Ontos to Barstow” Marine Corps Gazette May 1961 Ontology may be described as the science of reality, the investigation of the essential properties of a thing. What, pray tell, does this philosophical noun have to do with the profession of arms? With apologies to Plato and the gang, we will take the disciplines of ontology and apply them to the existing "thing" which has bastardized its name - Ontos. If consigned to the limbo of Barstow tomorrow, Ontos will have shared the distinction (with cotton khaki battle jacket) of being one of our Corp's more short-lived expressions of individuality. It is doubtful that the plaintive wails which attended the honorable retirement of the "60 mortar" would ever echo around the driver's hatch of the tracked "Dempster Dumpster." Rightly so, for weighing about the same as a healthy pachyderm, Ontos is a white elephant in our family of versatile weapons. This air-transportable orphan was adopted with sincerity by the Corps, during a period of helicopter intoxication, to replace the AT function of the tank within the division. It was adopted to provide the division with a realistic anti-tank weapon. This it fails to do. A weapon, to be worthwhile, should give us the maximum return in terms of its effectiveness for a minimum investment. I maintain that in this regard, Ontos is hardly blue chip stock. Six shares of BAT* stock give us a greater return on our money than one share of Ontos common. Even then, however, we have a weak investment portfolio. Let's look at the primary mission of Ontos, its anti-tank task. We must concede that Ontos can knock out tanks. Anybody's. If you have ever watched a trained crew operate you know what I mean. However, go beyond the guns and look at the weapon as a whole. Armor protection is insignificant; therefore, it cannot stand a slugging match. You may say, "Weaponry is ascendant over armor and not even the heaviest tank can withstand a direct hit from a modern AT gun." I maintain that Ontos can't even slug it out with a grease gun. One blast of automatic fire at the unprotected banks of guns will sever the exposed fire control system; leave the hull intact and us with $70,000 liability. At least with BAT*s it would take six bursts in six different directions to accomplish the same end. Shall we move on? Back-blast not only gives the nearby infantry a cracking good fright but tends to incinerate the unschooled to its rear. Admittedly, this is hardly a consideration in battle, but, more importantly, that impressive blast also tips your location to the enemy's base of fire (tank & SP). Needless to say, Ontos as a source of annoyance will be honored by immediate and unfriendly attention. Of course, here is where Ontos maneuverability comes into play and hasty withdrawal to defilade saves the day. But does it? Hardly. We have to delay and raise the travel locks to support the guns before we can move, else we will snap our multiple muskets into an attitude of decided embarrassment-pointing at mother earth. However, to raise these travel locks, the gunner must center the guns in azimuth and elevation while the driver must crank an archaic hydraulic system for an eternity until the locks marry with the tubes and allow safe movement. Reflect if you will, the action of that enemy base of fire during all this. Assuming that we are successful in eventually getting into defilade, where do we go from here? An alternate position would be logical, but remember that T-54 in the distance is wise to us now and his 100mm is looking in our direction. If we reappear nearby - whacko! Okay, insure that the alternate position is not in the immediate vicinity of the primary position. Full credit for your logic! It might work but in the meantime hasn't the enemy really beaten us at our own game? While we move the distance to an alternate site compatible with safety and surprise, we are out of action and the enemy's maneuver element has moved frighteningly close. Besides, the enemy is probably tracking our tell-tale dust anyway and our alternate position will prove as uncomfortable as the one in the first instance. Why not forget about the alternate position and break contact to a pre-selected position to the rear to contain any break-through? This is reasonable if we are willing to accept the fact that our major anti-tank weapon has been good for only one shot during a critical point in the battle. Of course, the psychological impact on the front line "snuffy" when he sees his major AT unit heading for the rear in the face of an armored attack might be a matter of concern. Also, in open country, our M-50 might be degraded with an enemy shot in the back during this rearward movement. And what about this open terrain, this rolling countryside so favored by a fire and-maneuver tank attack? Here we have our greatest Ontos liability. Our primary AT weapon sits basking in all the glory of its 1800 yard effective range while the opposition tanks crack away at us at ranges considerably in excess of ours. They are damaging us with their tanks long before we can employ our anti-tanks against them. Better lay the artillery for direct fire, Marines! Perhaps I'm unfair. I set the scene for the illustration and naturally it tends to support my views. How about a situation favoring Ontos employment? Consider close country where range counts for naught? How about the ambush capabilities of Ontos. Unsurpassed, are they not? The answer is quite so. It is a close country anti-tank weapon; it is an ambush weapon and little else, and this is the point. The Ontos violates the principle of economy of force. It is an expensive weapon restricted only to situations which favor its limited capabilities-defensive capabilities of ambush and short range. Does this return warrant the expense in terms of dollars, personnel, support and maintenance effort necessary to sustain an Ontos-equipped battalion? I say no. Leave the short ranges to the BAT*s and provide the AT battalion with a weapon which has the range and ruggedness to do battle with tanks before the infantry has to cope with them. Bernard E Trainor** 218 Cordoba San Clemente, Calif. – See more at: https://www.mca-marines.org/gazette/1961/05/lets-transfer-ontos-barstow#sthash.beosjQjp.dpuf *BAT = Battalion AntiTank [system] = 106mm RR in that time frame. It was a trilateral program [US, UK, CA]. Thank you for this definition Dr. Ken Estes, USMC(Ret.) who is a Foundation Board Member, oft-published author, and has contributed significantly to the discussion of the Ontos. |

|

M50 Ontos: The Forgotten Tank-killer By Brendan McNally - February 12, 2013

Frontal view of the M50 Ontos and its Marine crew during Operation Franklin in the Quang Ngai province of Vietnam, June of 1966. (U.S. Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections photo)

Sharing Options: It is the tradition in the U.S. Army to name its tanks after great generals. Over the years there has been the Stuart, the Grant and Lee, the Sherman, the Patton, the Pershing, the Abrams, the Sheridan, the Chaffee, and the Bradley. But there was one armored vehicle that was so singularly odd and strange looking; it didn’t get named after anyone, lest perhaps, some insult might be taken. Instead, the name it got handed was Ontos, the Greek word for “the thing.” It was an apt name. With its tiny chassis, tinier turret and six, massive, externally mounted recoilless rifles; the M50 Ontos had to have been the strangest armored vehicle ever to make it into the American military inventory. Except for some Marine Vietnam veterans, the Ontos is, today, almost wholly unremembered.

A M50 Ontos during a training exercise at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Va., Dec. 19, 1955. U.S. Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections photo. The reason has less to do with the Ontos’ battlefield performance, which at times was stellar, than it did with the fact that only about 300 were ever built, a little more than half of which survived up to the time of the Vietnam War. It meant there weren’t enough Ontos to engage the tactician’s imagination and so it never featured in tactics problems in the basic schools. There was never a military occupational specialty for Ontos crews. Officers might serve in an Ontos unit for a tour, but then they’d move on to something else and whatever they’d learned from it never really entered into the institutional memory. Another reason was that Ontos was designed as a tank killer, but since the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) only rarely used tanks, Ontos was used mainly as an ad hoc weapon. But fight it did, distinguishing itself at Hue, Khe Sanh, and countless other battles. For all its out-and-out eccentricity, Marines found it handy to have around because it was nimble and fast. Thanks to its relatively light weight, Ontos fairly glided through swamps and rice paddies, where heavier vehicles wisely feared to tread. And Ontos packed a punch that was way beyond its weight class. For this reason, the NVA feared it and avoided the Ontos wherever possible. If there was a general after whom the Ontos should have been named, it probably would have been Lt. Gen. James Gavin, wartime commander of the 82nd Airborne Division. After the war he wrote a book called Airborne Warfare, outlining his vision for using airborne forces in future wars. Part of it involved using air-transportable mechanized forces as a kind of light cavalry, capable of doing reconnaissance, and when necessary, laying extremely deadly ambushes against enemy armor. In the spirit of cavalry, such vehicles would have to sacrifice protection in favor of speed, agility, and ability to deliver serious firepower. The Ontos program began in November 1950 as a joint Army-Marine Corps program. The development contract went to Allis Chalmers’ Farm Machinery Division, with the work being carried out at the company’s Agricultural Assembly Plant in LaPort, IN. According to legend, the spec sheet they developed it from was only one-page long. Among the few things that it specified was that its running gear would be based on the M56 Light Anti-Tank Vehicle and that it would utilize the same six-cylinder, inline gas engine common to all the military’s 2½-ton GMC trucks. In 1953, the prototype was presented to the U.S. Army, and they immediately hated what they saw. They hated that it was so small and too tall and that there was not enough room inside it, either for the three-man crew or for ammunition for the recoilless rifles, of which only 18 rounds could be carried. They didn’t like that the turret was so shallow, really little more than a cast steel turntable and hatch in the middle. They hated that the six recoilless rifles that made up its armament were externally mounted and had to be reloaded from the outside. They didn’t like that the half-inch armor plating on the sides wouldn’t protect the crew members from anything larger than .50 caliber machine gun rounds, and that the underside’s armor plate was not even half that thick, making it totally vulnerable to mines or anything that might explode underneath it. The Army backed out of the project, canceling their share of the 1,000 vehicle order.

Two M50 Ontos from the 1st Anti-Tank Battalion move up to support a 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines patrol in the Quang Tin Province of Vietnam during Operation Iowa. U.S. Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections photo. The Marines, on the other hand, were not nearly so fussy. They liked that Ontos was so fast and agile and seemed capable of going anywhere they went, which was more than could be said about most tanks. They accepted that instead of being able to fight it out with enemy tanks, the Ontos would have to “shoot-and-scoot” to a place where it could safely reload. As for its pronounced lack of protection, they shrugged. For Marines, being shot at was nothing new. They placed an order for 297 Ontos. The production contract went to Allis Chalmers, which started building them in 1955 and finished in 1957, with the first vehicle accepted by the Marine Corps on Oct. 31, 1956. The Ontos’ official name was: “Rifle, Multiple 106mm self-propelled M50.” At its heart was the M40 106 mm recoilless rifle, a weapon which had been developed after World War II as a tank killer, based on the earlier M27, 105mm recoilless rifle, which turned out to have a number of key deficiencies. The rounds the M40 fired were not, in fact, 106mm, but 105mm, but were designated as 106mm to keep from being confused with the M27’s round, which was not compatible with the M40. The M40 had the accuracy, the range, a serious punch forward and a serious kick aft. During the Ontos’ testing at the Army’s Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, all six guns were fired at once and the backblast was so great that it knocked bricks out of nearby buildings and shattered numerous car windows. The powerful recoilless rifles’ accuracy was greatly aided by attaching .50 caliber spotting rifles to four of the Ontos’ six M40s. The rifle fired a tracer round whose trajectory, at least for the first 1,100 yards, was nearly identical to the M40s, and it marked the spot it hit with a visible puff of smoke. The spotting rifle’s own range was only 1,500 yards, and hitting targets beyond that required burst-on target and bracketing techniques of fire adjustment.

A M50 Ontos fires at snipers along the urban streets of Hue during the Battle of Hue City, 1968. The Ontos proved its value during the Tet Offensive. U.S. Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections photo. The first time Ontos was deployed was during the Lebanon Crisis of 1958. Since it was a peaceful intervention, it saw no action. Six years later it did go into combat during the American intervention in the Dominican Republic of 1964. There it encountered and promptly destroyed several enemy tanks, including a French-built AMX-13 and an old Swedish L-60. It was the only time the Ontos ever performed the mission it was built for. Then came Vietnam. In 1965, during the initial American buildup, the Marines sent over two anti-tank battalions equipped with Ontos. With no enemy tanks to fight, the Ontos companies were quickly spread out and attached to other units. The problem was, with no doctrine in place for them other than for fighting tanks, the Ontos were used or not used largely according to the whim of the commander of whatever units they were attached to. Though they quickly proved themselves as highly capable infantry support weapons, providing excellent frontal fire and flank protection, the Ontos had some serious shortcomings. After one or two would get destroyed by mines or rocket-propelled grenades, their unit commander often found his enthusiasm for them considerably dampened and relegated them to static defense duties. Another problem that plagued the Ontos was repeated accidental firings of its recoilless rifles because of too-tightly adjusted firing cables. Even so, the Ontos continued to be deployed supporting infantry. Using HEAT rounds, the Ontos was an excellent bunker-buster. But where it truly excelled was as an anti-personnel weapon. A “beehive” round was developed for the M40 that, upon exploding, unleashed a massive whirlwind cloud of nearly 10,000 steel flechettes. As a result, the VC and NVA were terrified of the Ontos and avoided it wherever possible.

A M50 Ontos leads commandeered vehicles during the Battle for Hue City, 1968. The Ontos was spearheading the effort to MedEvac and resupply Marines in Hue during the Tet Offensive. U.S. Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections photo. In December 1967, the Marines reorganized their anti-tank battalions and as a result, the Ontos units were all attached to tank battalions. By this point, the Ontos was becoming worn out. Treads and other replacement parts were becoming difficult to obtain. Increasingly, Ontos were being cannibalized to keep others operating. It was already obvious its days were numbered. Then, on Jan. 30, 1968, the NVA launched the Tet Offensive. It was one of the longest and bloodiest battles of the entire Vietnam War, nowhere as hard fought as in Hue City. For the Ontos, the battle was its shining moment of glory. After the American (2/5) and South Vietnamese forces cleared the south bank of the Perfume River, the 1st Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment (1/5) reached the Citadel. A number of Ontos were brought up and one by one, began taking out the buildings where the enemy were holed up. One of the Marine officers leading the siege of the Citadel later identified the Ontos as “the most effective of all Marine supporting arms,” in the Battle of Hue. At the same time, the NVA siege of Khe Sanh was also under way. With the threat of NVA armor anticipated, 10 Ontos were airlifted into Khe Sanh by MH-53 helicopter, and incorporated into its defense. There, the Ontos also performed with distinction. A year later, the Marines deactivated their Ontos units and the vehicles were handed over to the Army’s light infantry brigade. The Army used them until their parts ran out and then employed them as bunkers. What happened to them after that is largely unknown. After Vietnam, some were handed over to civilian agencies and used as forestry vehicles. A tiny number made it into collectors’ hands. Some are in museums. According to Mike Scudder, a former Marine who owns several, there are more World War I tanks in circulation than there are Ontos. This may not actually be true, since there are believed to be more than 60 Ontos sitting discarded in the desert on a Marine Corps reservation near China Lake, Calif. If they are still there, no one is saying.

|

|