|

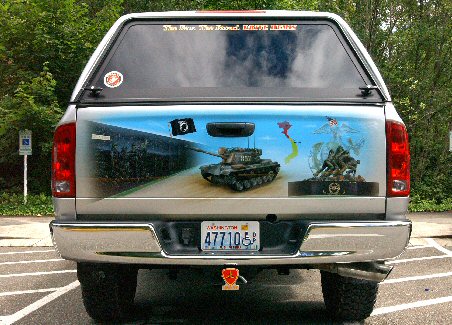

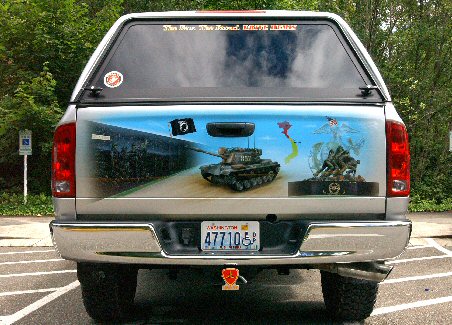

Carl "Flash" Fleischmann's Truck

By JO1(SW) Spencer Webster

Staff Writer

The loud rumbling of the silver-colored

Dodge Ram 2500 turned my head, but as the truck passed by me, the mural

painted on the tailgate captured my attention. It was not so much the

Vietnam Veteran theme of the images that caught my eye, but the loving

care in which they had been painted. Curiosity took me over and I had to

ask – what was the story behind the mural?

For Carl Fleischmann, former U. S. Marine, the story began in March of

1967 as he attended 13 weeks of Marine boot camp at Parris Island.

Following boot camp, he traveled to Camp LeJeune,

North Carolina, where he attended basic Infantry Training Regiment (ITR),

which taught him how to advance on hills and how to use various weapons.

After he graduated from ITR, he traveled

to California to attend the Tracked Vehicle School at Camp Del Mar at

Camp Pendleton. This is where he would learn his skills as a member of a

tank crew of the M48A3 “Patton” tank, which motivated Fleischmann a lot.

“For a 17-year-old kid, it was very interesting because there was this

52 ton vehicle that he could shoot, drive and maintain,” he said. “I was

very impressed with the tank. I remember driving on to a landing craft

and having it be dropped off and driving it to the beach.”

Fleischmann felt a sense of pride and ownership during his tank

training. “Kids, who before that, had only taken care of bicycles before

that, were now entrusted with a tank. Once you got your own tank, it was

a source of deeper pride; the taking care of it and keeping it in

top-running condition,” he said.

Following completion of his tank training in mid 1967, Fleischmann

attended 50-cal School and a linguistics and interrogation training at

29 Palms, prior to shipping over to Vietnam.

Fleischmann left his schooling a confident young man, but he discovered

he was unprepared for the reality of Vietnam. “When we got to Da Nang,

there was a rocket mortar attack on the airfield,” he said. “It was

pretty interesting but I was a kid again because I’d seen dead and

wounded soldiers and this scared me. It was sobering.”

He was taken, along with nine other people, to Phu Bai via helicopter,

where he was assigned to the Third Tank Battalion, Third Marine

Division, Headquarters and Service Company (H&S Co.) to re-supply

manpower for the tanks. Fleischmann’s role in H&S Co. was to provide

manpower, parts and supplies for the forward tank companies (A-C), which

were used for convoys, various patrols and covering support for the

infantry. The fast and furious nature of getting indoctrinated into war

mode, where he received his weapons, protective gear and information

about where he would sleep or where to go in case of attack, overwhelmed

him.

“During a watch, I found myself looking

past drums filled with dirt, sand bags, down a barrel of my weapon

through the barb wire and claymore mine field to the country side,” he

said. “This is real. We are not home and playing any more.”

In early 1968, the war presented an even

starker view to Fleischmann, when he found himself in a convoy heading

toward Hue (pronounced way) City. “Before we pulled out, it was quiet,

which was unusual and eerie,” he said. “Then, when we got to Hue City,

the Tet Offensive had started, where all the main cities of South

Vietnam were attacked and overrun at the same time by the North

Vietnamese Army (NVA). This was the first time I saw someone, a Marine,

advancing with us, shot right in front of me and it changed me. I

realized how fragile we are. When someone dies within 10 feet of you,

and you hear it, it gives you a different perspective.”

However, Hue City was not done changing Fleischmann’s life. He found

himself participating in house to house battles, something that had not

been done since the days of World War II. During one of these battles,

he, as the tank driver, noticed through a viewing hole an enemy soldier

as he pointed a rocket propelled grenade launcher at his tank.

“Before he shot, I turned the wheel (and the tank) to reduce the impact

of the grenade. The rocket hit, and the tank filled with smoke,” he

said, “No one inside the tank with me got hurt, so I got the tank back

to a safe area.” Fleischmann opened the tank commander’s turret and

discovered that his commander, Cpl. Robert Hall had suffered mortal

injuries.

“I took him back to the Military

Assistance Compound, Vietnam (MACV) Company Headquarters for Hue City,

trying to get medical assistance for him, but a corpsman came out and

told me there was nothing they could do for him,” he said. “I held onto

Robert, who was gurgling and basically drowning in his own blood as he

held onto me with what was a death grip on my shoulder until he passed

away.” Fleischmann took the death of his tank commander very hard,

because every member of the tank crew was part of a close-knit team;

they ate chow together, wrote letters together and talked of family life

at home.

“To have someone die in your arms and not

be able to do anything about it was brutal! I closed up and there was no

one I could talk to, especially as it took us a month to get out of Hue

City,” he said. “That was when I went hard – the enemy really became the

enemy – it was personal. Nothing bothered me after that and no one could

get close to me.” After he left Hue he was ordered to Quang Tri where he

and the rest of his crew traveled their separate ways, because the loss

had been too great and the memories too difficult, so they all asked for

transfers.

As a result, Fleischmann joined a tank

crew in C Co., commanded by Cpl. John Wear, where he participated in

patrols that led to the demilitarized zone (DMZ), Con Thien (pronounced

con-tea-en), Camp Carroll and Leatherneck Square. “He came to my crew as

the gunner, which was inside the tank,” said Wear, “and being inside of

the tank had an adverse effect on him because he could not see the

enemy. We were in several a static positions after six months and he

wanted to be on the ground, combating the enemy, up close and personal,

so he asked for a transfer.”

At that time, Fleischmann was six foot

tall and weighed 106 pounds, so he became a perfect candidate for being

a tunnel rat, which gave him an increased ability to meet the enemy on

his terms. “We got to go out on more patrols, day and night,” he said.

“We were the first in the towns and villages and if we found a tunnel, I

got to go inside first. I didn’t have the fear.”

A normal tour in Vietnam for Marines was 12 months but Fleischmann asked

for and received a 6-month extension and by his 18th month, he’d been

awarded three Purple Hearts, two for his action in Hue City and one at

the Cua Viet River. He returned to Camp LeJeune and was given a choice

of duty, and he chose duty closer to his home state of Connecticut at

Quonset Point Naval Air Station in Rhode Island, where most often, he

stood gate security as part of the Marine Barracks there. But shortly

after that, in late 1969, he was medically discharged.

“I fought for five years to get back into the Marine Corps but I tried

to adjust to civilian life,” he said. “I still wish I could have been

able to get back in.”

He returned to Connecticut at Groton, where he continued to work for the

U. S. government, but as submarine builder for Electric Boat, followed

by a move to Keyport, Washington, where he built torpedoes. Along the

way during his civilian life, he has suffered numerous illnesses that

were attributed to his exposure to Agent Orange, most recently; he has

recovered from prostrate cancer. For Fleischman, he may have left

Vietnam, but in every aspect of his life, Vietnam never left him,

especially the loss of his friend and tank commander, Cpl. Robert Hall.

“Over a year ago, I bought a 2004 Dodge 2500 4X4 pickup truck and I

wanted to do something special with it but I did not have an idea of

how,” he said. “I told my family I wanted something done – to remember

my buddy Marines; a memorial of some sort.”

His wife, Gail, son Carl and daughter Christa, got together over dinner

one night and decided on an initial design, which had been penned out on

a napkin, and showed it to Fleischmann, who liked it. The junior Carl

Fleischmann took the design to an artist/painter acquaintance, Tony

Crosta, who paints tailgates, motorcycles and bicycles in Port Orchard.

“I took their ideas and drew up a concept; took all the elements and

drew an initial drawing,” said Crosta, “based on conversations about the

whole story of the tank commander. I spent a day on research, looked at

a model of the tank he was in and put my heart and soul and time into

this project. Accuracy was important to me.” After Crosta completed the

project, he presented it to Fleischmann.

“I cried like a baby. The design they came up with was exactly what I

was looking for,” he said, “in fact, it exceeded my expectations.” The

truck is no longer a truck to Fleischmann or his family, but has become

a living memory of a long-dead but never forgotten friend.

“My family understands me and my

experiences a little better because of the truck,” he said. “When I cry,

they know why. To this day, I am afraid of losing people close to me.

Robert will always be a part of my life and he will be in Heaven waiting

for me. There are still things I cannot talk about with regard to

Vietnam, but this truck has opened me up for Robert.”

The power of the mural on the tailgate of the truck has spread to other

people, including the artist himself. “It gave me a new respect for what

they (Vietnam Veterans) went through,” said Crosta. “I hadn’t known

anyone who had been through that. It means a lot for me and I feel like

I have impacted a lot of people. I knew I did my job. People stop and

talk with me or leave notes on my windshield about taking photos of the

truck,” said Fleischmann, “so I know it affects people. At my house, the

Marine Corps Flag and the American Flag fly at the same time. I am proud

to be an American and proud to be a Vet. I wouldn’t change a moment in

my life, because it makes you who you are.”

Brian Nokell, Photographer, Naval Base

Kitsap - Bangor, Visual Information

|