2d Battalion, 9th Marines in 1967- “Hell in a Helmet”

Beth Crumley – August 1, 2011

Early last week, I received an email from an acquaintance of mine, an active duty Marine officer, who commented on my HMM-262 blog. He said he was pleased to see me writing on Vietnam, since the Vietnam veterans had been ignored, or held in disdain, for so long. He added that his father had been with Echo Company, 2d Battalion, 9th Marines in 1967. I was surprised to hear that, and a bit taken aback. I knew that was a hell of a year for 2/9… Operation Hickory, Operation Kingfisher, heavy fighting in the hills around Khe Sanh Combat Base, and at Con Thien. My curiosity got the best of me, and I started to look more closely at battalion operations for the 1967 period…and it is an understatement to say it was a hell of a year for the unit that called themselves “Hell in a Helmet.”

In the early spring of 1967, 2/9 was operating south of Hue. The commanding officer of Echo Company, Captain William B. Terrill, received word that his company was flying back to Phu Bai. Once there, he was briefed on the growing enemy presence around Khe Sanh Combat Base. Elements of the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines were reporting frequent contacts in the area, and it was believed that two NVA regiments were operating in the area. Echo Company was heading to Khe Sanh to reinforce the Marines already there.

Neither Captain Terrill, nor his seasoned commander of 1st platoon, Staff Sergeant Spencer Olsen, believed the reports of heavy NVA activity in the area. Said Olsen, “It seemed every time we were briefed about a new operation, there were two NVA regiments waiting for us. All of these briefings seemed canned.”

On March 7, much to the relief of the Marines of 1/9, Echo Company, 2/9 arrived at Khe Sanh. It was not long before they realized the reports of enemy activity in the area were not exaggerated.

Eight days later, on 15 March, SSgt Olsen received orders to conduct his second patrol. The first has taken Olsen and his Marines south of Hill 881S. This time, he was to scout the north side of the hill. The plan was to follow a trail west of the base, and in the course of a week, to cross Hill 861, and patrol the area north of 881S and west of 861.

Olsen’s patrol, comprised of about 40 Marines, departed the relative safety of Khe Sanh Combat Base near dusk. Moving in a staggered column, Olsen halted the patrol about a quarter of the way up Hill 861, and took the radio handset to report in. He later said, “Vietnamese voices filled every frequency….There was just so much NVA radio traffic in the area that it was bleeding over onto all my frequencies.” It was a portent of things to come, and it was, for the Marines, an uneasy, sleepless night.

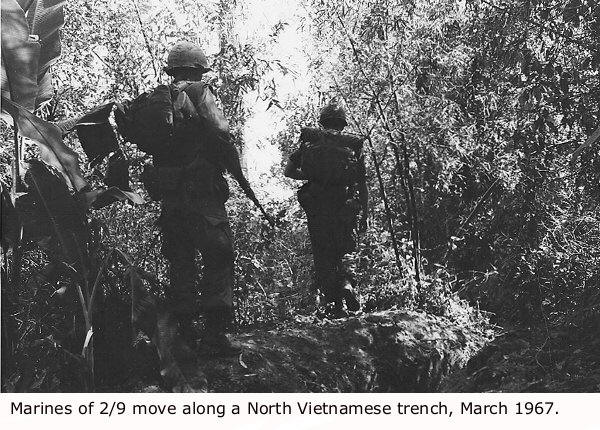

On the morning of 16 March, the patrol continued its advance up 861. Cautiously moving through thick vegetation, the Marines could hear Vietnamese voices. SSgt Olsen halted the patrol and called for artillery support. Within minutes 105mm rounds impacted the far side of the hill. As the patrol continued, the trail leveled off below the crescent of hill before it descended down the west side of 861. The lead squad, led by Sergeant Donald Lord, disappeared from Olsen’s sight. As they approached a fork in the trail, the point man, Private First Class George D. Johnson, asked “Which way?” Corporal Julian McKee pointed to the left. Thirty meters down the trail, they came to a second fork. As Johnson turned to ask which trail to take, he saw several hundred NVA. A blast of small arms fire killed Cpl McKee instantly. PFC Johnson was mortally wounded. As Private First Class Ivory Puckett watched his best friend dying, he opened fire. A momentary silence followed, then the hill erupted, spewing enemy fire on the Marines. Concussion grenades fell among them.

SSgt Olsen called for artillery support. Lance Corporal James Chase “started the rounds on the eastern slope of Hill 861 and walked them over the top.” As the rounds exploded, Olsen made contact with Marine air assets operating in the area, and handed the handset to LCpl Chase. Chase, who had never directed an airstrike before, brought the jets in but twice called for them to abort. The jets came in for a third time and released canisters of napalm. To Chase, it seemed the canister were far too close. In a second, the landscaped changed from lush, green jungle to one of flames.

SSgt Olsen now began to concentrate on assisting his wounded Marines. One of his corpsmen was seriously wounded. The other, despite shrapnel wounds to his arms and legs, continued to treat the patrol’s casualties. As medevacs were called in, Captain Michael Sayers, commanding Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, diverted a patrol and ordered them to Echo Company’s position.

Olsen had succeeded in gathering most of his casualties around a suitable landing zone. As a CH-46, escorted by Huey gunships, landed, a mortar round exploded. SSgt Olsen was catapulted through the air. He said, “Wide streams of blood were running down both my arms. There was so much blood…” Wounded by shrapnel in both arms and the backs of his legs, he was told that seven wounded Marines had gotten out aboard the helicopter. Incoming enemy mortar fire had, however, wounded several more. He called for another medevac.

As the second helicopter landed, mortar rounds once again pounded the Marines. Said LCpl Chase, “I looked around. The chopper was gone…Several newly wounded guys staggered around the LZ, blood pouring from their wounds. It was horrible.” SSgt Olsen was faced with a decision. Both times he had called in medevacs, the enemy had hit them hard, causing more casualties. However, there were simply not enough able-bodied men left to carry the wounded. He radioed Captain Terrill and told him they needed help.

By 1500, a column of Marines, a platoon from Bravo, 1/9 came into view. As they did, the unmistakable sound of incoming mortars was heard. The enemy fire had a devastating effect on the approaching Marines. As the smoke lifted, dead and wounded were strewn about the hill.

As the Marines worked to gather the dead and wounded into a perimeter, a third helicopter approached carrying additional troops from Bravo Company. One of them, Private First Class David Hendry, felt the helicopter shudder and saw holes appear in the fuselage. The CH-46 tumbled from the sky. It hit the ground nose-first, flipped and finally came to rest some 700 meters down the side of Hill 861.

Captain Terrill and his command group flew into the battlefield from Khe Sanh. Corporal Robert Slattery stated, “Dead and wounded Marines were everywhere. SSgt Olsen had that thousand yard stare of a man who’s seen too much death and destruction.”

It took the rest of the evening and into the night to evacuate the wounded. In the morning, helicopters arrived to take the dead. Subsequent patrols combed the area between Hills 881S and 881N. There was no sign of the enemy. They had simply vanished. Marine casualties totaled 19 dead, and 59 wounded, all of whom had belonged to Echo Company. Depleted by fighting, the company returned to Dong Ha on 26 March to rebuild.

In early May, Con Thien, south of the Demilitarized Zone, came under heavy attack. Enemy activity in the “Leatherneck Square” area intensified and while clearing Route 561 between Cam Lo and Con Thien, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines made contact with a large NVA force. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) authorized the III Marine Amphibious Force to conduct ground operations in the south half of the Demilitarized Zone. The planned attacks called for combined USMC-ARVN attacks along parallel routes. Code names for the operation were Hickory for Marine forces, and Lam Son 54 for ARVN forces.

By mid-May of 1967, a large force of US and South Vietnamese troops were poised south of the Demilitarized Zone. In total, some eight Marine infantry battalions, including two afloat, and five South Vietnamese battalions (three airborne and two infantry) were ready to go on the offensive. Among those was the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, which had arrived from Phu Bai on 16 May.

Operation Hickory launched on the morning of 18 May, 1967. 2d Battalion, 26th Marines, and 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, under the command of LtCol John Peeler, were supported by tanks from Alpha and Bravo Companies, 3d Tank Battalion. As they moved northward from Con Thien, 2/26 made contact with a large NVA force, estimated to be two battalions, positioned in well-defended bunkers and trenches. The right flank came under blistering automatic weapons and mortar fire. Casualties were heavy and the Marines of 2/9 moved up to reinforce the flank, immediately engaging the enemy. As night fell, the Marines broke contact and pulled back to evacuate the dead and wounded.

That night airstrikes hit enemy positions and as the day dawned on 19 May, artillery fire fell on enemy defenses. Both battalions jumped of in the attack at 0700. Within minutes, the advance of 2/26 was halted from withering fire to the front and right. 2/9 moved forward against light resistance and was able to relieve the pressure on 2/26’s right flank. By 1030, the Marines had overrun the enemy bunker complex and continued the advance.

Three hours later, Company H, 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, on the easternmost flank of the advance came under heavy attack near the intersection of Route 606 and 561. Heavy automatic weapons and mortar fire emanated from the east. Shortly thereafter, they began taking heavy fire from a tree line 60 meters to the front. Several Marines in the point squad had been shot and were lying in the open. Corporal Robert Gillingham ran through savage enemy fire to rescue one of the wounded Marines. Hit three times in the effort, he dragged the man to safety, but later succumbed to his wounds. He was posthumously awarded a Navy Cross for his actions.

Tanks from Alpha Company, 3d Tank Battalion, were brought in to support the attack. Almost immediately the first tank, “Earth Moving Mama,” was hit. The gunner was killed instantly, and the tank commander was mortally wounded. A second tank moved into the fray and was immediately hit by RPG fire, knocking it out of the battle. Captain Robert J. Thompson, commanding Company H, moved the entire company forward to retrieve the dead and the wounded. As the company pulled back, he called in supporting arms. The action left 7 Marines dead, and another 10 wounded.

The next day, 2/9 faced Gia Binh, an abandoned village some 2500 meters northeast of Con Thien, where the NVA has established an extensive bunker complex off Route 561. Accompanied by tanks, 2/9 started the attack at 0930. One flame tank torched the bunker while another fired canister rounds and machine guns. Surprising, enemy resistance was very light. The NVA had pulled back from their fortified positions around Con Thien.

The command chronology for the month of May states, “During Operation Hickory, well-equipped and well-trained NVA troops fighting from fortified bunkers and positions were encountered. These positions had interlocking fields of machine gun fire and defensive concentrations of mortar fire. Camouflaged and placed at strategic locations, they formed formidable obstacles to friendly offensive movement.”

Casualties for the operation totaled 22 killed in action, and another 116 wounded.

By 28 July 1967, 2/9 found itself involved in Operation Kingfisher, yet another operation along the DMZ, designed to block NVA entry into Quang Tri Province. Reinforced by a platoon of tanks, three Ontos, LVTEs and engineers, the Marines moved north along Route 606. Companies E and G provided security on the flanks.

Moving through a narrow stretch of land bordered by the Ben Hai River on the west and north and a stream to the east, terrain dictated that the tanks remain on the road. Thick vegetation made movement on the flanks very difficult. Unbeknownst to the Marines, who would be forced to return by the same route, the NVA were already moving units into positions covering Route 606.

On the morning of 29 July, 2/9 reached its objective. By late morning the battalion began moving south out of the Demilitarized Zone, led by Echo Company. At 1115, the enemy detonated a 250-pound bomb buried in the road, wounding 5 Marines. The engineers soon found a second bomb and destroyed it.

As the second bomb detonated, the NVA opened fire with small arms, machine guns and mortars, beginning a running battle that lasted until darkness fell. The NVA had established several strong points along the road. Some Marines dove off the road, only to land on NVA booby traps that had been placed there overnight.

Given the situation, and the terrain, the tracked vehicles became a liability rather than an asset. Company F was ordered to establish a helicopter landing zone to evacuate the dead and wounded. When the tanks entered the area, the enemy rained down a torrent of fire. Machine guns, RPGs and mortar fire swept the entire landing zone. Corporal Miguel Rivera Sotomayor, wounded by shrapnel knocked out an enemy machine gun position. He braved the enemy fire to man an M-60 when the gunner was badly wounded. When he ran out of ammunition, he picked up a rifle and continued to fire before being badly wounded. (Corporal Sotomayor survived and was later awarded a Navy Cross for his actions.) In addition to the casualties they had already taken, another 7 Marines were killed, and another 31 were wounded.

By late afternoon, Echo Company and Command Group A managed to break through the enemy gauntlet. Two squads of Echo Company could not move due to intense enemy fire that had killed 2 Marines and wounded 9 others. Other companies of 2/9 were unable to move, pinned down by enemy fire and with too many casualties.

Hotel Company, commanded by Captain Frank Southard, pulled back to join with Company F. The two squads from Echo joined them, as did two squads from Golf Company. The remainder of Golf Company, bringing up the rear had successfully fought off the NVA during the day, but found themselves separated from the main body by 1000 meters.

Mike Company, 3d Battalion, 4th Marines moved back up the road to defensive perimeter. In the morning, meeting no resistance, they were able to link up with the remainder of 2/9. Once again, the NVA had disappeared into the jungle.

Helicopters began evacuating the wounded and the dead. The After Action Report submitted by 2/9 clearly states,

“It is believed the mission of the enemy force was to isolate the battalion, separate the column and then destroy - as an initial phase in the long sought after victory over the forward Marine outpost at Con Thien. His concept of operation

was to conduct ambushes at several strong points, utilizing terrain features to his advantage, at these, the enemy had pre-registered mortar concentrations. In all cases the strong points were covered by intense automatic weapons fire.”

In a three day period, 2d Battalion, 9th Marines had suffered the loss of 23 killed in action and 191 wounded. Those Marines who survived returned to the “Leatherneck Square” area harboring feelings of bitterness and betrayal.

Throughout August, the battalion operated in “Leatherneck Square,” a free-fire zone bordered by Con Thien and Gio Linh to the north and Dong Ha and Cam Lo to the south. It was a relatively quiet time for the battalion. However, by September, enemy activity began to intensify around Con Thien. Said UPI photojournalist David Powell, “When I think of Con Thien, I get a knot in my stomach and I feel echoes of the fear I felt. God, it could be terrifying.”

On the morning of 12 September, 2/9 was awakened by a barrage of 82mm mortar fire. Several Marines were wounded. As the helicopters arrived to medevac the wounded, the battalion was subjected to second barrage. Both the commanding officer, Lt Col William D. Kent and his executive officer were wounded.

By 15 September, the battalion moved to some 2000 meters south of Con Thien, closer to the main supply route. Pounded by enemy fire, the Marines also endured heavy rains. Said Lance Corporal Jack Hartzel, “I don’t remember a day in which we didn’t get hit with incoming rounds of some sort. We also suffered something that was almost unheard of elsewhere in South Vietnam. It was called “shell shock” and it was not unusual. The constant pounding every day could make you do nuts. You would sit there on edge, wondering if the next round that came in would have your name on it. We were in holes in the mud. Our holes would fill with water; we’d have to bail them out four or five times a day. We also had immersion foot and your feet would bleed and hurt like hell. Then there was the damned mud! You walked in it, you sat in it, you slept in it and you even ate it. There was just no escaping it.”

Enemy fire was so heavy, so constant, that the Marines of 2/9 were not regularly resupplied. Over the course of nine days, Con Thien was hit with more than a thousand rounds of artillery fire, rockets and mortars. At one point they were forced to scrounge in their own trash pits for something to eat.

Throughout September, the enemy kept up the pressure and Marine casualties mounted. Con Thien averaged 50 wounded and 2 Marines killed by incoming every day. 2/9, now operating outside the wire, was taking almost as many casualties.

On the morning of 25 September, at 0715, Con Thien was pummeled by hundreds of rockets, mortars, artillery rounds and recoilless rifle fire. 122mm rockets landed in the midst of 2/9. Said LCpl Hartzel, “The thing I remember about September 25 that really sticks in my mind is a picture of a Marine sitting in a puddle of blood and battle dressings on a poncho with his legs blown off from the waist down. He was numb from morphine and in shock from loss of blood. He was smoking a cigarette very calmly as if nothing had even happened. He was waiting for a medevac. He probably died on the chopper ride back… Our platoon arrived at Con Thien with 45 men. When we left we only had twelve. Now you wonder why we called it “The meat grinder!”

The following day, 2/9 was pulled out of Con Thien after two months in the field as part of Operation Kingfisher.

Late fall would find the battalion embroiled in Operation Kentucky, and once again, caught in a fierce day long battle near Gia Binh, where they had faced the enemy in May.

It had, indeed, been a hell of a year for the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines. The coming year would prove just as difficult, if not more. The battalion would see action in Operation Scotland, the defense of Khe Sanh Combat Base. They would also see action near The Rockpile and Vandergrift Combat Base.

There is no doubt that those Marines who served in 2d Battalion, 9th Marines were extraordinary. Those who survived lived together, fought together, and all-too-often bled together. I find myself reminded of the Saint Crispin’s Day speech in Henry V:

“From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember'd;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother;”

Let us remember those who served with 2/9. Let us remember their hardships and their sacrifices. And rest assured, they will not be forgotten.

https://www.mca-marines.org/mcaf-blog/2011/08/01/2d-battalion-9th-marines-1967-hell-helmet